Welcome back to Week 11 in my weekly reports analyzing the Covid-19 pandemic and its effects on the country, higher education and study abroad. This newsletter is a version of the post on my blog, Off the Silk Road. For those of you reading this on my blog, Off the Silk Road, I have also launched a newsletter, where these reports can be sent directly to your email each week. Click here to subscribe.

Last week, I looked at states that have been relatively successful at controlling the spread of the virus, as well as examined some unanswered questions for colleges to reopen in the fall. This week, we will discuss the state of the pandemic nationally and critically look at some colleges’ fall reopening plans.

There’s a lot of material to go through (as per usual), so let’s get straight to it.

A national look

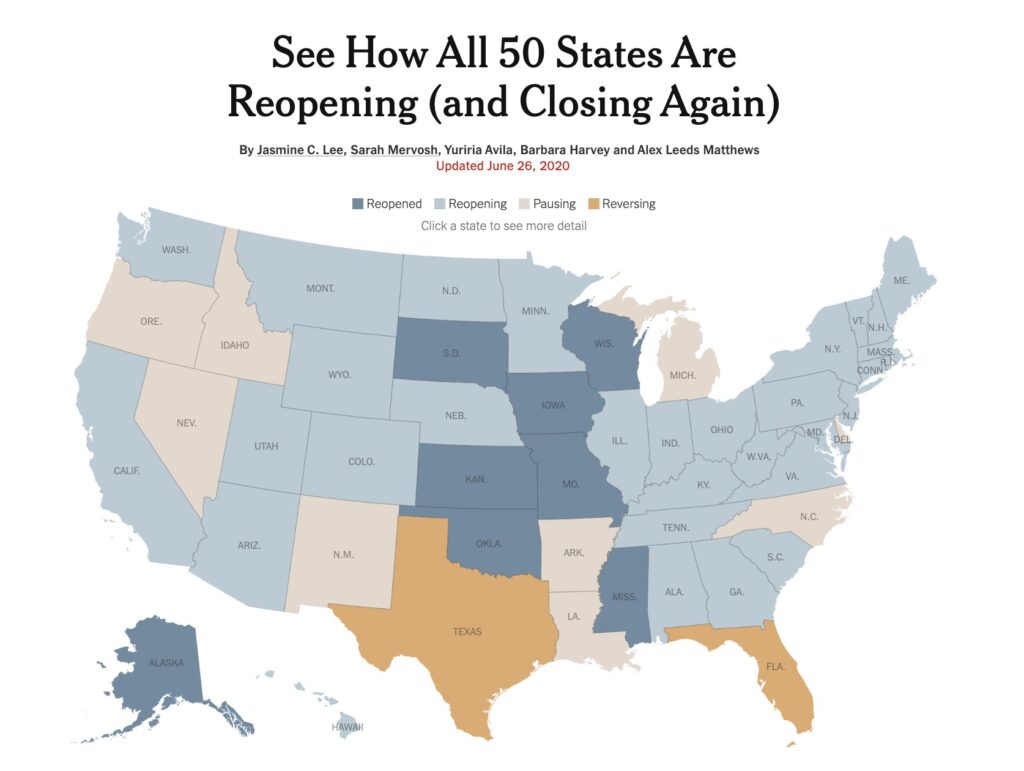

On a national scale, our efforts to flatten the curve have failed. 37,077 cases were confirmed in the U.S. on Thursday, the highest single-day case count ever recorded. 32 states have increasing case counts, with 11 flat and 7 declining. “The U.S. is at a crossroads,” Dr. Anthony Fauci said this week. “Americans can either be part of the problem or part of the solution.” Coronavirus is back in the news as the main headline and does not appear to be taking a summer vacation. Masks are only a band-aid. Whatever we have been doing as a nation for the past three months has not been working. Sure, contact tracing is important, but at this scale it is impossible to contact trace so many cases for this intervention to be effective. With asymptomatic spread turning out to be a key method of transmission, we must rely on social distancing and mask wearing to be critical to saving lives. We know what to do and we are not doing it. These are very serious issues, and as Anderson Cooper says, “this is not a joke.”

With cases on a consistent increase (the lowest daily case count in the last few months has been around 17,000), the death rate seems to be going down. Why is this? This is because deaths lag cases by a few weeks, which means we may see an uptick in deaths in July. It’s possible that this new influx in cases is connected to Memorial Day or general summer activities. Take a look at this graph from data in New York City, illustrating clearly defined curves of cases, hospitalizations and deaths weeks apart. I fear that the increase in current cases will lead to a spike in deaths a few weeks from now.

Let’s take a moment to discuss the actions of the president and his administration. Trump’s strategy of deny, lie and defy has brought this nation to his knees. Aside from the deadly action of cramming thousands of people for rallies in Tulsa and Phoenix, he fails to understand that testing is vital for controlling viral spread. Ending federal funds for testing claiming he told officials to “slow the testing down” is a catastrophic mistake. Pretending the virus is not there or not testing does not solve the problem. It’s like saying if you don’t step on a bathroom scale you don’t gain weight. Additionally, the fight and politicization of masks must stop. While I do not support this president, he is even failing in his attempts to win. Dozens of Secret Service agents and staffers have been ordered to quarantine after attending his rally. In order to achieve such a “transition to greatness,” we need to have a national strategy for testing and strong policies for social distancing. There is no political will or public support to go back to the lockdowns we had in March, but I fear this is coming to be our only choice. As the viral spread slows in the Northeast, “Trump Country” is being hit hard, as seen on these graphs.

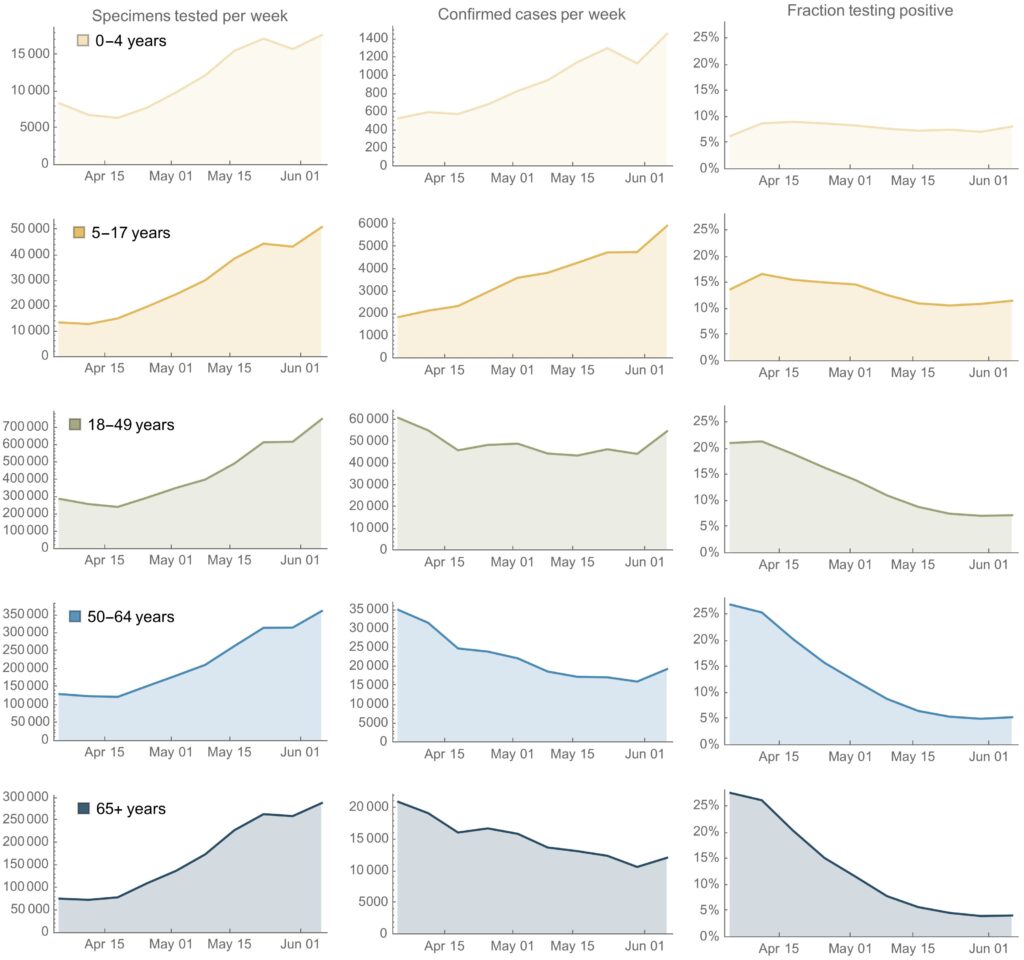

This is now the millennial pandemic. We’ve seen a profound shift in the age of newly confirmed cases. In Florida, the median age of new Covid-19 cases fell from 65 in March to 35 this week. There are a few explanations for this new change:

- More testing — while we are testing more, hospitalizations are up, which would mean that the increase in hospitalizations is not due to the increase in testing.

- The elderly are being more cautious. This is possible, because the percent positivity rate in the elderly has dropped.

- Young people are being less cautious. In reality, while it is a combination of all three of these factors, this one seems to be contributing the most to an increase in cases.

There are three roles for testing: personal health, surveillance and mitigation. Personal health is simple; if you have symptoms, get a test. Surveillance and mitigation can be used as ways to detect disease prevalence in a community, but in many areas of the country, we still cannot scale testing up enough for these goals to be accomplished. Antigen tests (where results are processed much faster than the current PCR tests) are still not available on a wide scale.

The failure of federal leadership is not just the fault of President Trump. His own vice president lies to the public regularly about our progress on this disease and presented no plan or modeling at the first task force briefing this past Friday, the first in 60 days. As his own task force considers a new public health strategy — pooled testing, this could enable the country to conduct 10 times more tests than it does currently. It isn’t just the federal government. We live in a country where a large portion of the population does not believe in science and rejects the consensus that wearing a mask will save lives. A new study shows that that infection and mortality rates are higher in places where one pundit who initially downplayed the severity of the pandemic — Fox News’s Sean Hannity — reaches the largest audiences. Another study shows that “a society’s ability to effectively mobilize in response to a crisis of the nature and scale of Covid-19 depends in large part on its political leadership.” This has been a crisis of communication and those states who have succeeded in communicating the facts have been able to reopen safely. By instructing the public to consume disinfectant, Trump clearly fails at effective communication and will result in killing Americans in the process. As states have begun to roll back reopening plans and others impose quarantines on travelers from high-risk states, the IHME model predicts 179,106 deaths by October 1, with 146,000 as a possibility if 95% of the population wears a mask in public. IHME director Dr. Christopher Murray predicts a possible “second wave” starting in August and continuing through the fall. With temperature checks essentially useless for controlling spread and a high level of correlation between age and asymptomatic spread (the younger you are, the more likely you are to spread the disease asymptomatically), the next two weeks will be critical for the model to potentially modify its predictions. Is it possible that this next phase of the pandemic will mainly affect young people and we will not see a large uptick in deaths? Possible, though I fear we must prepare for the worst.

As usual, we have seen more studies published and new pieces of information now available to help us better understand Covid-19. Let’s take a look at some of the highlights.

- According to the CDC, 10 times more people may have had the virus than was previously reported.

- Airlines, including American Airlines, have begun to sell their flights to full capacity.

- Parties — not protests — appear to be spreading the virus.

- Restaurant spending appears to be a predictor of where the virus will spread next. JPMorgan Chase & Co. found the level of in-person spending in restaurants three weeks ago was the strongest predictor of where new cases would emerge. Similarly, higher spending in supermarkets indicated a slower spread, suggesting shoppers in those regions may be living more cautiously.

- In the middle of a pandemic, Trump is attempting to eliminate health insurance (Obamacare) for 23 million Americans.

- A new CDC study shows that infectious people may produce viral bioaerosols that remain infectious for long periods.

- CDC records show only 15 of the 121 cruise ships that arrived in U.S. waters since March 1 did NOT have coronavirus on board.

- Pregnant women may be at increased risk for severe illness from Covid-19, the CDC reports.

- Fraternity parties in Mississippi and a bar in Michigan can now be considered “superspreader events.”

- The CDC study on the infamous UT-Austin student spring break to Cabo, Mexico finally came out, underscoring the importance of detailed contact tracing. 20% of infections were asymptomatic, while symptoms were detected in positive and negative tests.

- Two infections in China were linked to a public toilet.

- A new study finds that 80% of infections nationally went undetected in March.

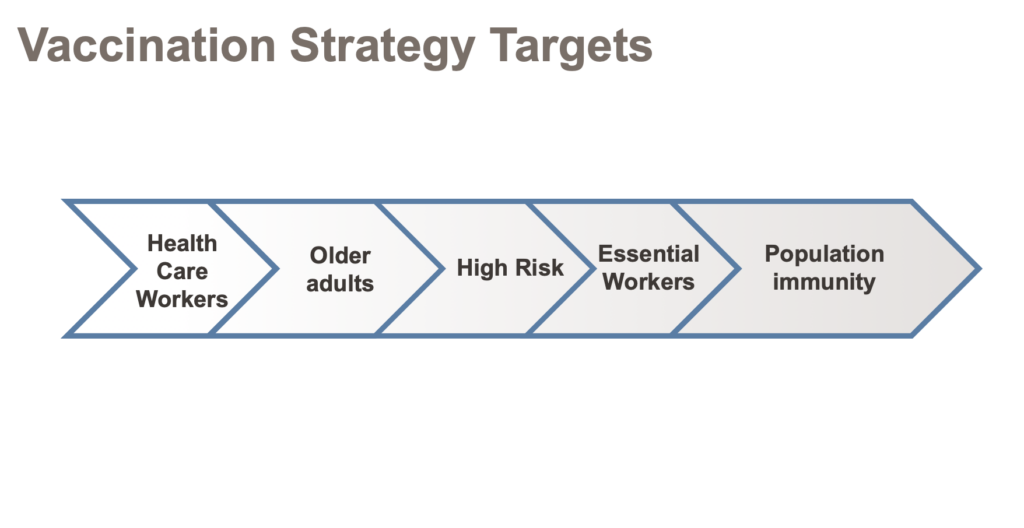

I wanted to finish this section with a quick update on the distribution of a potential vaccine. This diagram shows the general order in which a vaccine will be distributed, whenever a successful candidate is found.

This is just a snapshot of our nation’s trajectory in the past week. It is truly alarming to see not only an increase in cases in states such as Arizona, Texas, Florida and California, but an increase in hospitalizations and a lack of a clear public health strategy on the national level and in many states. It is time for partisan politics to be put aside and in the absence of a federal plan, for state governors to take the necessary steps to save lives. And to all the young people out there, please understand how risky each outing at a bar can pose on not just you, but every person in this country. The United States needs leadership and a strategy. We cannot lose three jumbo jets’ worth of people every day until there is a vaccine. Like manifest destiny, the virus has gained footing going west. We need an effective plan to turn the country around, or we will all pay the price. That price will be incredibly dangerous. I call on everyone to make sacrifices in their behavior and communicate effectively to others to do the same. Do not waste these next few weeks in doing your part to stop the spread.

Having laid down the groundwork on the national scene, let’s take a look at the latest developments in higher ed.

Higher education

This week we have seen more schools announce fall plans, and like last week, many of them point to reopening in person. Last week, we examined some of the unanswered questions in the first round of decisions. This week, I’ll discuss some plans of particular interest, as well as some new frameworks from which to think about reopening, having read enough mentions of the words “unique, unprecedented and different.”

The strongest reopening plans from what I’ve seen include three components:

- Pre-semester (re-entry)

- During semester (funky fall)

- Post outbreak (toggle term — where a college would switch back to remote instruction)

First, let’s talk about re-entry. If this virus enters a college campus in large quantities, it will spread like wildfire. We’ve seen this from positive tests in college football, where it took one outing to a lake (outdoors) and one event in a player’s apartment to spread.

It’s important to think of testing and screening as two entirely different concepts. Testing involves actually testing individuals (through a PCR or antigen test), while screening involves a series of temperature checks and symptom reporting. Both are valuable, though frequent testing for mitigation is most ideal. Colleges could provide excellent case studies for the nation if they have robust testing programs.However, we still do not know for many schools if faculty and staff will be tested, if contacts of confirmed cases will be immediately tested and how health insurance (or lack thereof) could affect testing availability. Middlebury College is requiring all students to quarantine in their homes for two weeks prior to their arrival to campus. The school will then test all students on arrival, place them in “room quarantine” until test results are returned, then allow the students to be confined to the campus for another week until another test. This strategy is quite well developed, though I question what will happen if a student tests negative in the first test but could be harboring the virus. As we learned, the U.S. Army tested a cohort of 640 new recruits and instructors for Covid-19 upon arrival at Fort Benning, Ga. All but four tested negative. Eight days after training started, and after a 14-day monitoring period, 142 of them retested positive. This could very well happen on any campus, especially for those with students coming from high levels of infection. Even though school does not start until August, the University of South Carolina has seen an increase of 79 cases in eight days, mostly attributed to off-campus restaurants and bars.

Let’s assume that colleges are able to get past the re-entry stage. Fundamental changes to all aspects of academic and social life have already started. Teaching and learning will have to be reimagined, with some professors putting masks as a grade requirement in course syllabi. For some faculty, the privilege of teaching remotely is personal, with PhD students at Boston University being instructed to return to campus or risk losing their stipends. Amherst College has ordered tents for outdoor instruction. An incredibly detailed report from Cornell University suggests that instructors should not include attendance as part of their grade for two reasons: (a) students may be absent from class because they are placed into quarantine; and (b) grading attendance will incentivize students to attend class even when they do not feel well, which is the opposite of what we need them to do for public health and safety. This is important. According to one simulation, a lecture hall that normally seats 149 people in this simulation holds just 16 students, 11% of capacity. The University of Michigan proposed, but failed to pass, a $50 “Covid fee” to be levied on all students for the semester. As colleges in Virginia seek $200 million for testing, a disparity has begun to emerge between schools with abundant resources and funds and schools without.

In addition to academic life, residential and social life will experience major changes. The University of Pennsylvania has developed a campus compact for its students to follow, which includes policies on masks, social distancing and general health and safety. Emory University has said their rules will be peer-enforced. Students at the University of Georgia have pushed for a face mask requirement. Harvard University is planning to bring 40% of students back for the fall, though selection criteria remain unknown. While students at Brown University have indicated that they support the use of testing and contact tracing, as reported by my colleague Kayla Guo, it remains unknown how effective these tools will be to detect an early round of infections (since I assume all colleges will not test wastewater). The University of North Carolina will not refund students for housing if they must depart campus early. Students at the University of Michigan are “cautiously pessimistic” about the fall and their social contract. “I feel like it’s too much to ask from college students, especially how last semester went,” one student said. “Even as the University was shutting down and quarantine was starting, people were still going to parties (and) Rick’s was still open. There’s no way they could possibly enforce it.”

Two key metrics for all members of the college community to know are: (1) what percentage of courses will be online and (2) what percentage of beds will be filled on campus (for social distancing reasons). The first question, in particular, may influence students’ decisions to return. If a student’s classes are mostly online, they may choose not to return to campus and complete their coursework for the fall.

We have discussed in previous reports a toggle term/amphibious autumn threshold — what it will take for colleges to switch to online instruction in the event of an outbreak. Francie Diep at The Chronicle of Higher Education found one college in the nation (Florida A&M University) that has given any sort of specificity: a cluster of three cases would trigger some sort of action. Yet, they do not specify what location this will be — a dorm, coffee shop, party? And there is not even a designated action —only that there will be “additional restrictions to mitigate transmission risks.” Higher ed professor Robert Kelchen advocates for every college to craft a plan that includes publicly known metrics to dictate when colleges will change operations in some form. “Allowing data to determine plans may also provide colleges with some protection against calls to close as soon as the first few cases come to campus in the fall,” he said. These data points could include:

- Number of known cases among students and employees

- Number of known cases in the county

- Capacity to quarantine on-campus students

- Available space in local hospitals (beds, ICU space, and ventilators)

- Fatalities could be a measure, but it is probably too gruesome to include even though all deaths may be impossible to avoid

I would encourage all institutions of higher education to think critically of the “toggle term” option and formulate detailed plans to account for a possible, even likely outbreak, should they choose to open for the fall.

It is vital to consider the impact that colleges have on their surrounding communities. For many local communities, they are extremely vulnerable to infection due to their age or other underlying health conditions. While many local businesses greatly rely on college students, some people in the local community have mixed reactions about reopening plans. To help quantify this risk, I created a Covid-19 vulnerability index for every county in New England using four factors: the percentage of the population over the age of 65, the percentage uninsured, the prevalence of obesity and the prevalence of smoker use. These were factors chosen due to their increased risk of infection. It is worth noting that there is little correlation with these factors and actual confirmed cases in New England. However, it is still an important way with which we can think about vulnerability. On this map, you can explore the counties with the 11 New England Small College Athletic Conference (NESCAC) schools overlaid. Colby College in Waterville, Maine is the most vulnerable, with a vulnerability index of 0.933.

As colleges formulate plans for the fall, professor Kevin McClure at the University of North Carolina Wilmington argues that they must explain the “why” of reopening — how they see reopening connecting to their mission statement and purpose. “Presidents should show they are thinking about higher education’s responsibility to the public good,” he said. “They should articulate how their plans contribute to the fight against the spread of Covid-19 and how they are responsive to the disproportionate toll the virus takes on Black, Indigenous, and Latinx communities.”

Even among peer schools, approaches can vary greatly. For example, while Middlebury College has formulated plans to bring students back with quarantine and testing, Tufts University has announced that they will have classes continue in-person after Thanksgiving, discouraging break travel. Bowdoin College has made plans to bring four groups of students back to campus:

- New first-year and transfer students

- Students with home situations that make online learning nearly impossible

- A very small number of senior honors students who cannot pursue their pre-approved projects online and require access to physical spaces on campus, and can do so under health and safety protocols

- Student residential life staff

I applaud Bowdoin’s leadership for this model of mostly all classes online (with the exception of small first-year seminar classes). With only a quarter of students on campus Bowdoin’s model delivers the education to those who need the in-person experience the most (for high-level research and first-year retention purposes), and dramatically reduces the risk of infection. I am currently working with student researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles to attempt to quantify the marginal risk brought on with each additional student on campus and will report back results. In the NESCAC, of which Bowdoin is a part, the schools’ plans vary considerably, as seen in this map.

It is worth noting that in some states where the pandemic continues to surge, college presidents have begun to consider alternatives. In a radio interview, University of Arizona president Robert Robins said he would weigh the decision with “great deliberation.” He commented if he had to make the call today, he would not proceed with reopening. Arizona State University president Michael Crow has remained flexible. “In any event, we’re ready to reassemble,” and “Zoom only,” he said. “Whatever comes, we’re going to be ready.” Higher ed professor Brendan Cantwell has devised two predictions for colleges:

- They keep planning for in-person operations (the University of Michigan announced in-person just this week!) and then pull the plug sometime just before students return (early-mid August).

- In-person operations resume but end quite quickly because of virus spread and we have a repeat of the spring (during which I was very sympathetic to the plight of administrators, but I, and I suspect others, will be less understanding a second time).

Marketing professor and higher ed thought leader Scott Galloway said “it’s time to end the consensual hallucination between university leadership, parents, and students that in-person classes will resume in the fall.…We must play a key role, as we always have, in arresting, not enabling, the greatest health crisis of our era.” In my opinion, based on the current trajectory of the pandemic nationally and its continued disease prevalence, colleges must seriously consider the possibility of a remote fall. I fear that a last-minute transition would be incredibly disruptive and believe that faculty could spend the summer developing thoughtful, innovative, interactive and experiential learning opportunities. At Amherst College, “a number of faculty are preparing new and topical courses exploring the pandemic, and race and racism in the United States,” according to a report in the college’s student newspaper. We can use this time as a community to provide students with meaningful learning opportunities and strive to create an education that will ensure students have a memorable and fulfilling semester. Weighing the health risks is incredibly important, and we must prepare for both scenarios.

With university presidents essentially playing the role of governors with their decision making, it is an incredibly complex decision and I thank anyone in higher education administration for their hard work. There are many unanswered questions at this point and in the coming weeks, more will become clear. In a tweet earlier this week, I cautioned against over-analyzing situations and making foolish assumptions on various aspects of campus life based on what we know now. It’s important to remember that the situation remains incredibly fluid and modeling and plans will change. We take every day as it is.

Study abroad and international travel

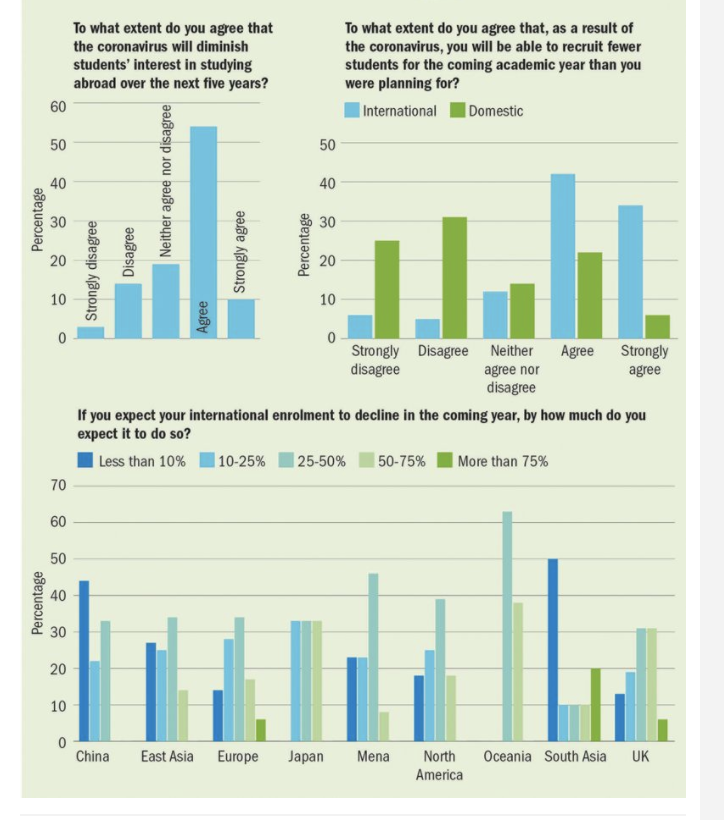

I still don’t think most study abroad programs will be running for the fall. This week, Syracuse University, Ohio State University, Tufts University, the University of New Hampshire and Harvard University announced fall international program suspensions. While we are unsure as to the specifics of the new EU travel restrictions, as well as U.S. visa restrictions, I would say it is a fair assumption that many international students will face extreme difficulty returning to campus in the fall. Most consulates for entry into the U.S. are still not processing visas, regardless of the reason for travel. Colleges and universities must support their international students, who are currently experiencing complex and tough situations. A letter written by international students to the administrators at Bowdoin College asks for education equity with regards to courses, living situations and healthcare. From a survey of 200 universities around the world, it is evident that the loss of international students and abroad programs will have long-lasting effects, including financial and cultural.

The Good Stuff

Let’s roll the clips of the good stuff. In my usual tradition, I feature my favorite stories from the week. Let’s go with the Top 10.

- The New York Times examines 100 days without sports.

- A high school senior works as an essential worker, serving truck drivers keeping America’s infrastructure running.

- Remember the TikTok grandma from Iowa who bought all the tickets to Trump’s Tulsa rally? She’s now working for the Biden campaign.

- The Barcelona Opera House opened for a performance to 2,292 plants. “What a thyme to be alive,” as CNN’s Jake Tapper writes.

- The team at the Daily Californian investigates where Berkeley students go after graduation and in what sectors are they employed.

- After three months, New York City barber shops are open again.

- Roller skating is back.

- New York Governor Andrew Cuomo and his daughters look back on their time together during the early stages of the pandemic.

- In perhaps what is the most in-depth account of Trump’s visit to Arizona from a student newspaper, Piper Hansen at Arizona State reports on the day’s events. Her work is incredible, as always.

- Hamilton is coming to Disney Plus on July 3.

Conclusion

I am deeply concerned and alarmed at the direction the country has taken to slow the spread of the pandemic. I fear that the data we have seen this week are the beginnings of a downward turn where outbreaks could spiral out of control. As Dr. Fauci has now been blocked by the White House from making too many media appearances, I am incredibly worried that our communication for public health has failed and our viral spread trajectory will be too hard to change. As a consequence of these national results, I remain skeptical of many colleges’ plans for fall reopening and urge those in power to make careful, calculated decisions. The scariest part in all this? We know what we can do to save lives. And we’re just not doing it. The fact that “anti-science bias” is rampant in our society should be a national crisis, and it is our duty as Americans to save ourselves. Getting sick is not an option. Yet we seem to present it as one. We must continue to follow the advice of doctors and medical experts, and charge our fellow Americans with the utmost responsibility to make a difference. The lives and futures of all of us depend on it.

I’d like to thank all the student journalists with whom I have the pleasure of working. In the next weeks and months ahead, they will become ever more important in chronicling their colleges’ decisions for the fall and beyond. Support their work by reading it.

My best to all for good health.

Like what you see? Don’t like what you see? Want to see more of something? Want to see less of something? Let me know in the comments. And don’t forget to subscribe to the weekly newsletter!

For more instant updates, follow me on Twitter @bhrenton.