Welcome back to Week 4 in my weekly report on what I’ve read this week on the Covid-19 pandemic and how I see some possible ways going forward. You can read the first report here, the second one here and the third here. Like last week, we’ll be focusing on three major topics: a national view, higher education and study abroad.

There’s a lot to go through this week, so let’s get straight to it.

A national look

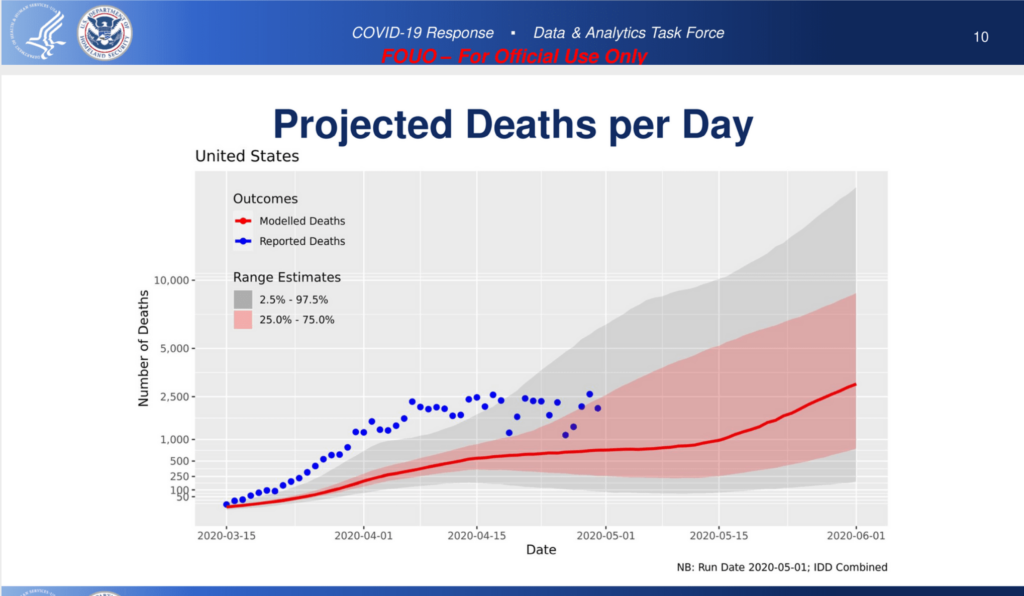

A few weeks ago, the White House released guidelines stipulating that states should wait for a 14-day decline in cases before moving to the next phase of lifting some restrictions. It seems that no state has waited to achieve this metric, with over 43 states opening some form of their economies at the end of this week. It was most recently reported that the White House has buried recommended CDC guidelines for opening the country. This vacuum of federal guidance is particularly concerning, even as internal CDC models predict a dramatic increase in fatalities and up to 2,500 deaths a day by June. Let’s remember British statistician George Box: “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” But still, there is reason for concern.

The key here is to get the reproduction rate of the virus down. For some states, that has been done through various measures, social distancing being one of them. However for others, this has been less successful. Cases in the Midwest continue to increase, even as states open up. Now could warm weather help? IHME says that with every 1º increase in temperature, average transmissibility could decrease by 2%. Now why are these models going up? Here’s what the IHME model accounts for:

- Mobility

- Population density

- Testing

- Temperature

Density makes sense. This simple graphic I’ve created shows the basics of transmission.

Let’s talk about testing. Governor Jay Inslee of Washington said on CNN that “not testing before reopening is like crossing a busy street with your eyes closed.” Even John Oliver and Patrick Star agree testing is necessary.

Testing not only enables us to find who to treat and isolate, it also gives us more information on the virus’ spread. Remember our goal is not to eradicate the virus. We need to contain it to a manageable level. We cannot afford to shut down again. Positive testing rates need to be below 10%. This enables us to pick up cases of mild disease. I’d argue these people are as important, as they may be able to spread with asymptomatic transmission. States should come up with testing plans to test their most vulnerable, those in hospital or nursing home settings, and then the general population.

It’s all a question of risk. How do we best mitigate risk? Limiting exposure to the virus is key. It’s out there in our daily lives. This is why it’s important to stay home. You all know this. The President doesn’t seem to understand it. There is no federal plan, and nothing matters until that is remedied. Why are other countries so successful? Because these plans are not implemented at a state/provincial level. The states are looking to guidance from the federal government.

Let’s talk about contact tracing. How does this work? You are assigned a case investigator from the health department of your local area.

- You self-isolate in your home

- Investigator draws up a list of close contacts through an interview with you

- They call the list of close contacts and tell them they may have been exposed and should self-quarantine

Relatively speaking, social distancing is a blunt tool. Additionally, remember that it can take a few weeks to see a spike in cases.Testing and contact tracing enable greater precision. We need more of those.

Some other news: a new study has shown the disproportionate effect of the virus on the African American community. The eyes could be an easy entrance route for the coronavirus. Immunity passports may not work. The New York Times has said their staffers will most likely not return until September 8 at the earliest. Travel from New York could have spread the outbreak to other places in the country.

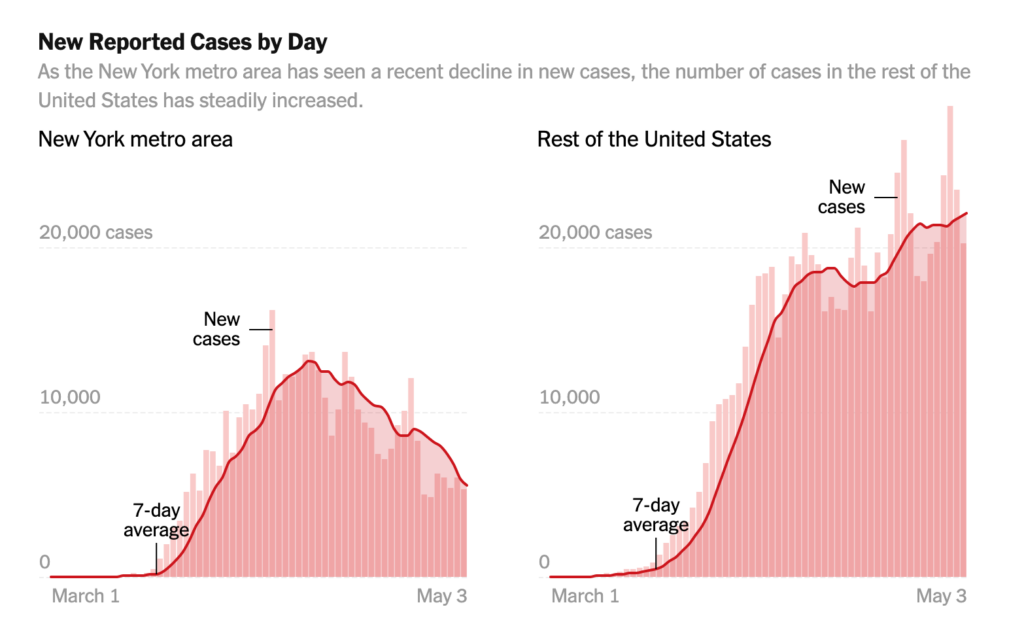

This graph has caught our attention and shows how when you take out new cases in New York, cases nationwide are increasing. This is why it is important to stay vigilant.

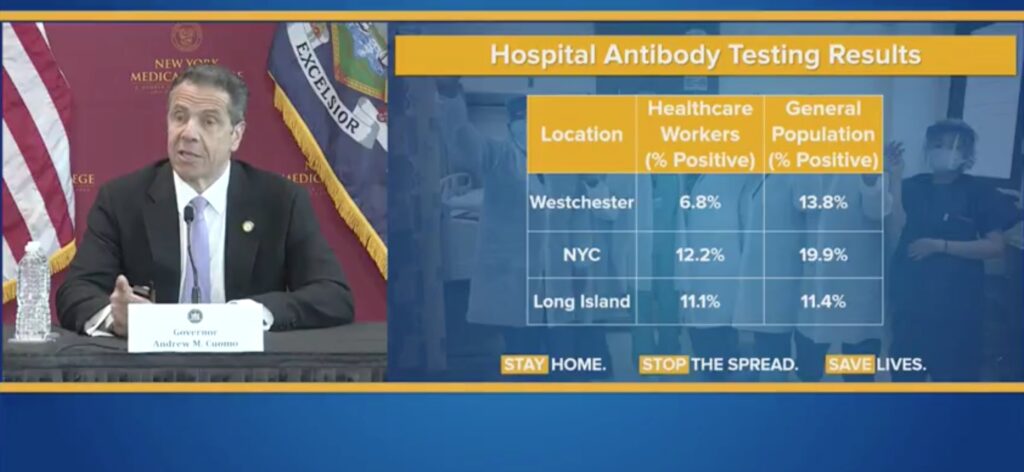

In a press conference on Thursday, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo shared results from an antibody study on healthcare workers.

The percentage of healthcare workers who have antibodies are about the same or lower than the general population in an area.

Key points, according to Cuomo:

1. Our healthcare workers must be protected

2. Masks, gloves and sanitizer work! (This assertion can be applied to the general population as well.)

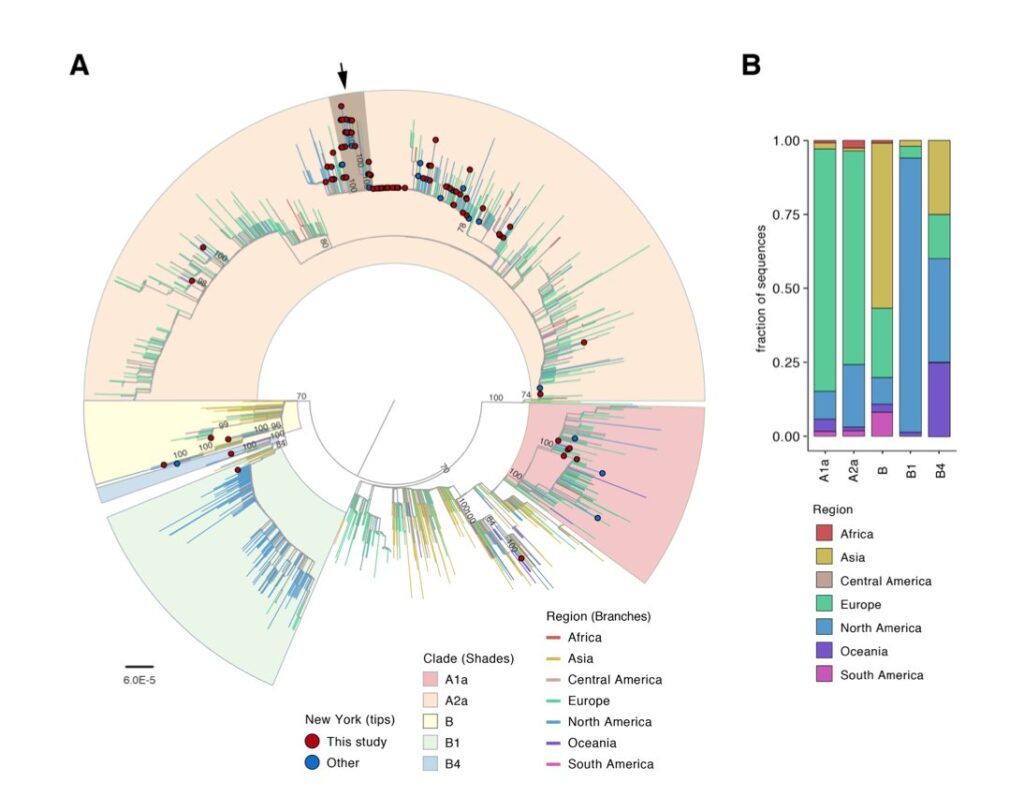

We’ve also seen how many viral strands in New York can be traced back to strands in Europe. This shows that while some of the West Coast cases are linked to China (due to a high number of flights between the West Coast and China), the East Coast cases mostly came from Europe. None of this is surprising to me.

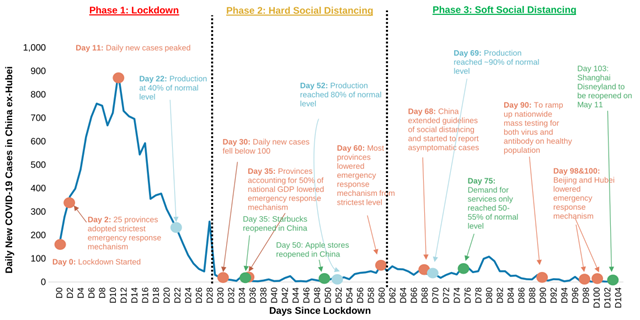

For updates on the China scene, this Morgan Stanley graph shows us a timeline that the U.S. could adapt for reopening.

What are some key metrics for reopening? In Vermont, Department of Financial Regulation Commissioner Mike Pieciak outlines what Vermont continues to monitor.

- Syndromic surveillance – those with Covid-19 like illnesses

- Rt – viral reproduction rates

- Percentage of positive tests

- Hospital bed capacity

Additionally, states must look to their neighbors. This virus knows no borders.

I wanted to finally look at some states’ plans for reopening that I believe were quite detailed. Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer’s MI Safe plan is successful for three reasons:

- Regional approach

- Phased approach with key metrics

- Steps that must be met to move onto the next stage

Similarly, Maine Governor Janet Mills’ plan shows checklists for various businesses.

Higher education

In colleges’ minds, it’s a balance between risk of reopening and viral spread and economic hardship. Why?

- Data from my colleague Olivia Gieger at Amherst College show that the vast majority (80%) of Amherst students would take the semester off if courses are remote for the fall.

- If a college cancels the fall completely, financial losses are too significant.

As a result, 74% of colleges in the Chronicle of Higher Education’s report have said that they will open for the fall. Now, those could change, and many are waiting to see what form that will be.

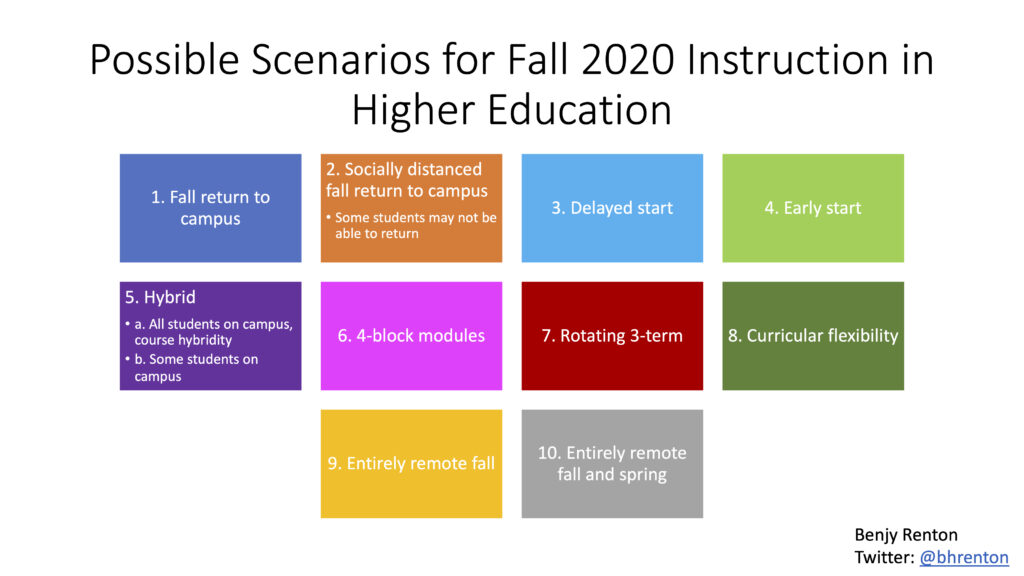

With that, I’ve created some scenarios using various college examples that we’ve seen this week.

Let’s analyze them in order.

- Fall return to campus

This assumes that a college will return in-person instruction in September, without any disease control restrictions. In my opinion, this is highly unlikely.

- Socially distanced fall return to campus

This assumes that a college has all students who are able to return to campus meet for in-person instruction. Social distancing restrictions could be in place, such as limits on large gatherings, spaced out desks and use of face masks on campus. Schools must consider the fact that international and immunocompromised students may not return and should plan remote instruction opportunities for them. This model could also mean a staggered return to campus, though this seems unlikely to accomplish much — while students are staggering move-in, they’re still all on campus at some point. However, in my opinion, it is difficult for colleges to limit social gatherings or trips off campus. While it may work in China, containing students to a college campus is very difficult in the U.S.

- Delayed start

A delayed start would give a college the opportunity to see how the pandemic progresses, if the school has confidence that this delay would result in a definite return of some sort of instruction in the fall.

- Early start

The University of San Diego and Purdue University have proposed this model. The fall would start in mid-August and end before Thanksgiving, without a break, to ensure that students could finish fall classes before the end of the flu season. In my opinion, this is a risky move and rather pointless, since an outbreak on campus could happen at any time.

- Hybrid

This model can be divided into two parts. One model is a course hybridity model, where some courses are in-person and some courses online, while all students will be on campus. Why is this a good idea? Simple. Research from Kim Weeden at Cornell shows that in the context of Cornell, when removing courses with 100+ students (taking them online), the percentage of student-pairs that can reach each other in three steps declines from 92.1% to 77.5%. When removing classes with 30+ students, that percentage decreases to 20.7%. While this is not an epidemiological model, and it is hard at this stage to quantify what defines “close contact” in a class (students on the opposite sides of the room are less likely for viral transmission), it does show that moving larger courses online decreases the risk of viral transmission. However, Professor Weeden’s model does not account for social interactions or any interactions outside of classes.

The second hybrid model is for some students to take courses online at home and others to be on campus. This would decrease the number of students on campus. However, questions arise from this model: How would a college choose who stays on campus and who doesn’t? Which courses would be online?

- 4-block modules

This model was pioneered by Beloit College in Wisconsin and has since been employed by Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, among others. It divides the semester into two blocks, where students take two courses each block. There are numerous benefits to this. It offers schools the opportunity to start with one module online and then the second in-person. With students taking two courses instead of four, it decreases the amount of contacts a student could theoretically have on campus and allows for greater faculty flexibility, since many are concerned for their own health. In my opinion, this is a viable option. It is worth noting at this point that these models can be combined to fit an institution’s needs; for example, social distancing can be used in tandem with any of these, and a block model can be combined with a delayed start.

- Rotating 3-term

After rocking the higher ed community with her New York Times op-ed, Brown University president Christina Paxson presented this new model for possible instruction. A college would shift to fall, spring and summer terms, with students on-campus and taking courses for two of the three terms. I suppose this is similar to Darmouth’s D-Plan. This model would decrease campus population density, with no more than 75% of the student body on campus at a time, according to the Brown Daily Herald. A course hybridity model could also be employed, with large classes online and smaller classes in-person However, questions arise: How does a college choose which students return when? What happens in the terms students are not taking classes? Brown’s provost says “this could be done by offering online internships with alumni or no-fee online classes.” This is a difficult model to digest for me because of those two main questions.

- Curricular flexibility

For institutions with winter terms or other short terms, these special terms could begin first, possibly online. My colleague at Williams College, Rebecca Tauber, reports on this as one of Williams’ options. This is a pretty open-ended model — schools could customize this however they would like. This would enable schools to do some sort of delayed on-campus start, which could be beneficial. In my opinion, having some of the fall on-campus, if possible, is better than no fall at all.

- Entirely remote fall

This is exactly as it sounds. Colleges should survey students to gauge interest in participating in remote courses for the fall. From my experiences, it doesn’t seem too popular.

- Entirely remote fall and spring

This is also exactly as it sounds. In my opinion, it is unlikely.

Regardless of which model (or a combination of a few) colleges choose, schools will have to be flexible and creative in their course delivery. Absolutely nothing is off the table, as Stanford University has even proposed holding classes in outdoor tents. Many detailed plans must be made for residential, dining and academic spaces. Additionally, states may still be enforcing quarantine periods for those from out-of-state. It’s all a question of risk — how schools can abate as much risk of viral transmission as possible while remaining true to their academic missions. In the coming weeks, we may see schools beginning to choose one of these models. Institutions may even form coalitions with which to adopt models together. In my opinion, one model does not fit every school nationwide. Here are some factors that could impact which model a school chooses:

- Liberal arts colleges vs. research universities

- Size of university

- Rural/urban location

- Location (state)

- Percentage of out-of-state students

Located in the Northeast and chairing a group of student journalists from nearby colleges, I frequently follow our peer schools in the region. Northeastern University in Boston has announced plans to reopen for in-person academic instruction and residential living in the fall. The University of New Hampshire has done so as well, in addition to the University of New England in Maine. In the coming weeks, I will hopefully be providing more maps and graphics to show the decisions of various colleges. Using the decisions issued by summer camps could also be an interesting metric to predict college openings for the fall, since they feature similar close contact and residential situations.

This week, the University of California at San Diego released a wide-ranging and ambitious plan for a return to campus in the fall, including widespread testing of students and the ability to detect an infection with just 10 positive cases. We will have to see how nationwide testing and laboratory capacity will be in the fall, which could determine how feasible this arrangement could be across colleges and universities nationwide.

Finally, I wanted to caution against misinformation and misleading rumors. They’re all out there — don’t believe them or draw to conclusions too quickly. Even overanalyzing a college’s decision could be pointless. You’ll know when you know — take it every day at a time.

Study abroad and international travel

Not much to report here for this week. Will be back next week with more possible updates. I hold my case that the chance of study abroad programs running in the fall seems unlikely.

The Good Stuff

In my weekly tradition, I’ve included this section with my favorite pieces from the week.

- A morgue worker buys flowers to place on the bags of patients who have lost their lives.

- A five-year-old boy was pulled over in Utah for driving to buy a Lamborghini in California. Quarantine seems to be doing some crazy things to people.

- The IT department at Indiana University about how their IT department has adjusted to the influx in calls.

- An inspiring high school journalist in Florida is determined to keep her paper running for one last deadline.

- White House photographers get creative in their shots.

- Spike Lee’s amazing new short film on New York.

- Former Michigan Daily editor-in-chief Maya Goldman’s piece in Vogue on how she celebrated her Zoom graduation. I’ve so enjoyed working with Maya and her co-editors at the Michigan Daily. Congrats to all in the class of 2020!

Conclusion

We continue to persevere with our country’s fight against the pandemic and its effects on higher ed. We can’t let up now, especially with warmer weather and increased mobility. We must look at the situation on a day-by day basis.

I’d like to thank all the student journalists with whom I have the pleasure of working. You are all truly an inspiration and it is a pleasure to read your work.

Let’s all keep doing what we’re doing and we’ll get through this together. My best to all for good health.

Like what you see? Don’t like what you see? Want to see more of something? Want to see less of something? Let me know in the comments.

For more instant updates, follow me on Twitter @bhrenton.

2 Comments

Mike Kiernan · May 9, 2020 at 1:06 pm

Another start model to suggest, if you have time for a chat.

Where We Stand with Covid-19 — June 12 - Off the Silk Road · June 13, 2020 at 10:17 am

[…] take this moment to revisit models I proposed on May 8, showing 10 options for colleges in the […]

Comments are closed.